Here are some of the actual objections we have received from Protestants regarding papal primacy, and our responses in turn.

Objection 1:

Peter never made such claims for himself. Indeed, in Luke 22:24-34 when a dispute took place between the disciples as to who would be the greatest, wouldn’t it have been easy had Jesus just said to Peter, “You will be my 1st Father of the church”.

Answer:

It is true that Jesus never explicitly states that St. Peter is the first Father of the Church. However, neither does he explicitly state many things that are nonetheless true.

For example, he does not state that He is the 2nd person of the Holy Trinity or—in fact—that the Trinity exists at all, but it is nonetheless true. It is however implied, and papal primacy is the same here.

Jesus response in Luke 22:24-34 is about being the greatest in the sense of service; it is not concerned with worldly hierarchy, and the two should not be mixed.

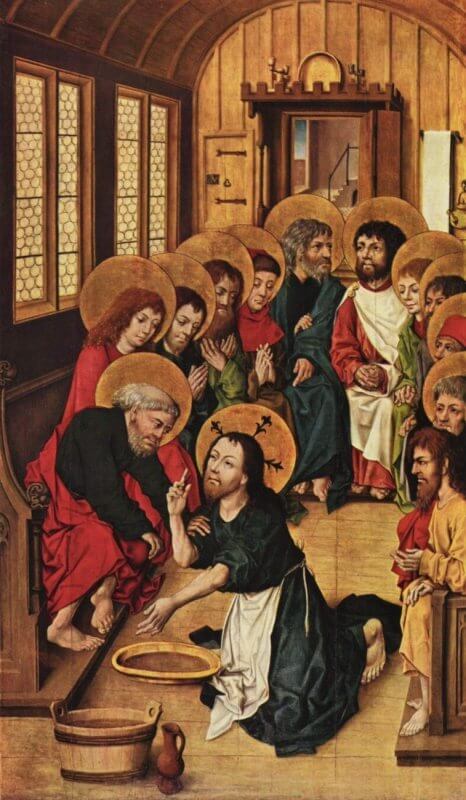

For example, Jesus himself is said to have “made himself nothing, taking the form of a servant” (Philippians 2:7), yet this in no way detracts from his authority in the Church.

Jesus tells us that, “The greatest among you must become the youngest, and the leader like one who serves” (v26). He then goes on in the same passage, singling out Simon St. Peter, saying: “Strengthen your brothers and sisters” and, also, that St. Peter’s “faith will not fail”.

Thus Jesus models true servant leadership and specifically instructs St. Peter to do the same. He, therefore, implies St. Peter’s primacy in instructing St. Peter to be the greatest servant of them all.

Pope St. Gregory I (pope from 590 to 604) was the first pope to use the phrase “servant of the servants of God” to refer to himself and, after the 12th Century, the title came to be used exclusively for the Pope.

There are other examples in Scripture where St. Peter’s primacy is more clearly demonstrated. For example, St. Peter (and St. Peter alone) is specifically given the keys to the kingdom of heaven (Matthew 16:19), as well as being the only disciple charged to feed Christ’s lambs and sheep, which included the 11 other Apostles (John 21).

As well as this, St. Peter is made the rock on which the Church is built upon (Matthew 16:18). Moreover, every time the names of the Apostles are listed, except for Galatians 2:9, St. Peter’s name appears first. In Matthew 10:2 it explicitly says that St. Peter is first. It is also St. Peter who chooses a replacement for Judas Iscariot. No other disciple is given these specific leadership duties.

Objection 2:

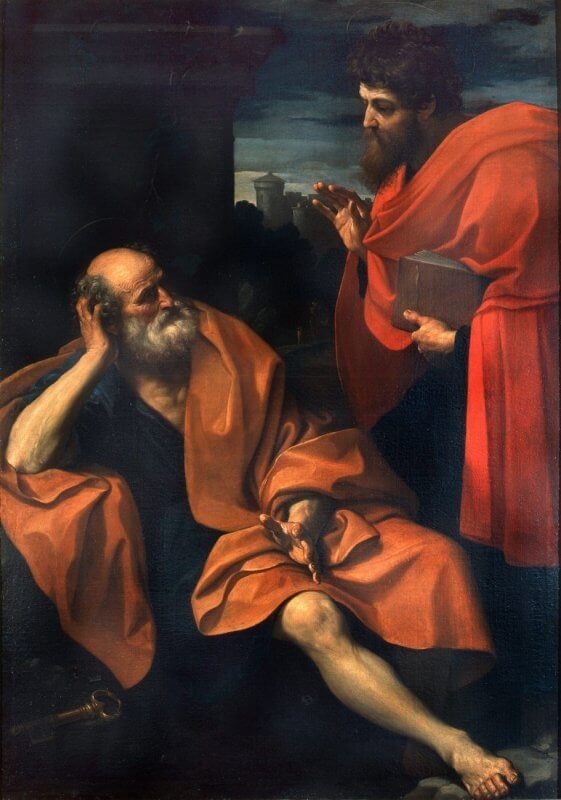

Peter may have been recognized as part of the leadership team in Jerusalem, as Paul records in Galatians 2:7-10, but he was in error at times and had to be rebuked by Paul as verse 11 states.

Answer:

I think there is a misunderstanding here. Nowhere does the Catholic Church teach that the Pope cannot ever be wrong. This is not what papal primacy entails. There have been many times where a Pope has said something that has later turned out to be false.

For example, in the 17th Century, Pope Paul V—for various reasons (and alongside other theologians, philosophers, and scientists at the time)—rejected Galileo’s theory that the Earth revolved around the sun. Obviously, it turns out he was wrong to maintain the Ptolemaic geocentric model which taught that the sun revolved around the Earth.

The Catholic Church does teach, however, that in very specific and unique circumstances, the Pope can speak without error. As paragraph 891 of the Catechism of the Catholic Church says, “The Roman Pontiff, head of the college of bishops, enjoys this infallibility in virtue of his office, when, as supreme pastor and teacher of all the faithful—who confirms his brethren in the faith he proclaims by a definitive act a doctrine pertaining to faith or morals.”

There are two key parts to this text: “by virtue of office” and “faith and morals”. I’ll briefly discuss the second of these points first.

According to the Catholic Church, the Pope, as Christ’s vicar on Earth, is able to proclaim the truth without error if it is on the subject of faith and morals. It also has to be said ex cathedra, meaning “from the chair”.

In Acts 15, the Apostles meet to discuss whether the new Christians needed to be circumcised. This was a matter of faith and morals. The Apostles did not get their Bibles out and debate and (inevitably) disagree with each other. Rather St. Peter, filled with the Holy Spirit and being preserved from error, proclaimed that circumcision is not necessary for the new Gentile Christians. The Apostles do not even question that he was right.

The Catholic understanding is that this is what happens not only in Acts 15 but in every subsequent Church council.

The Catechism also notes that the Roman Pontiff enjoys this infallibility “in virtue of his office”. That is to say, the Pope was not infallible before he was ordained as Pope; before he becomes Pope, he does not have this ability.

Do we see any Scriptural evidence for this? Yes, I think we do.

In the Old Covenant, we know that God granted special graces to the priests, especially the high priest by virtue of office. For example, in John 11, John tells us that, “He did not say this on his own, but as high priest that year he prophesied that Jesus would die for the Jewish nation” (John 11:51). John here hints that because Caiaphas was high priest, he was able to prophesy.

In Matthew’s Gospel, Jesus tells us that the Pharisees were teaching authoritatively simply by virtue of sitting on Moses’ seat. “The scribes and the Pharisees sit on Moses’ seat, therefore, do whatever they teach you and follow it.” (Matthew 23:2-3a) Jesus says here that because Pharisees are in fact Pharisees, they have authority to teach.

Jesus goes on to say, “Do not do as they do, for they do not practice what they teach” (Matthew 23:3b). Christ is making it clear here that even though they are hypocrites, the Pharisees and scribes have authority to teach by virtue of office; i.e. that they “sit on Moses’ seat”. It is the same in the New Covenant, with the priests and high priest.

Objection 3:

The Roman Catholic Church claims that Peter was bishop of Rome, but there is no Scriptural evidence for this.

Answer:

It is true that Scripture does not tell us that St. Peter was bishop of Rome, but that is because Scripture only records part of St. Peter’s life; if something is not in Scripture, it doesn’t mean it is automatically not true.

For example, it would be wrong to say, “It is not true that many of the Apostles were martyred because there is no Scriptural evidence for it”. We know that the Apostles were martyred because there is historical evidence outside the Bible for it. The same can be said about St. Peter and Rome.

St. Irenaeus of Lyons, halfway through the 2nd Century writes, “The very ancient, and universally known Church founded and organized at Rome by the two most glorious Apostles, Peter and Paul.”

In 190AD, Clement of Alexandria wrote, “Peter had preached the Word publicly at Rome.”

I could also quote Jerome, Eusebius, and Clement. The evidence seems to be clear; St. Peter definitely went to Rome, and being an Apostle, the historical data strongly supports the claim that he was a bishop too.

Objection 4:

There was never intended to be a hierarchical position in the church of “Father” (Pope) as bishops and deacons were the only offices recognised. Peter never made any sort of elevated claim for himself whatsoever.

Answer:

To say that there was never intended to be a visible hierarchical position in the Church is a very big claim to make without substantiation.

After all, in the Old Covenant, God established a priesthood with a head; the high priest. It cannot be completely out of the question, therefore, to assume that likewise in the New Covenant there is also a priesthood with a visible earthly leader.

Some Protestants believe that Christ just abolished that structure, yet there is no Scriptural or historical evidence, nor logical reasons for this.

Jesus himself said that he did not come to abolish, but to fulfill the Law (Matthew 5:17). The Scriptures clearly point towards St. Peter being the leader of the Apostles (Matthew 16:19, John 21:15-17, Matthew 10:2). Early Christians—people who were trained by the Apostles themselves—testify in the 1st and 2nd Century to papal primacy.

For example, in 200AD, Clement of Alexandria wrote, “The blessed Peter, the chosen, the preeminent, the first among the disciples, for whom alone with himself the Saviour paid the tribute [Matt. 17:27], quickly gasped and understood their meaning. And what does he say? ‘Behold, we have left all and have followed you.’”

Clement, writing in 221AD said, “Be it known to you, my lord, that Simon [Peter], who, for the sake of the true faith, and the surest foundation of his doctrine, was set apart to be the foundation of the Church, and for this end was by Jesus himself, with his truthful mouth, named Peter, the first fruits of our Lord, the first of the Apostles; to whom first the Father revealed the Son; whom the Christ, with good reason, blessed; the called, and elect.”

The great theologian St. Augustine of Hippo also had a similar understanding. In his commentary on John, he writes, “Who is ignorant that the first of the Apostles is the most blessed Peter?”

These are all people living about 100 years after the Apostles, in an almost identical culture, and where the Romans are persecuting Christianity—there was no reason to lie and no possibility for Roman corruption in the Church, therefore. Yet their view of St. Peter is crystal clear; St. Peter was the first among the Apostles.

Objection 5:

My understanding is that the Apostles teaching was the rule for several centuries after the death of the original Apostles and that the Church of Rome did not come into existence until early in the 4th Century. Thus to claim apostolic succession from Peter is a complete falsehood.

Answer:

This is a common assertion made by Protestants, but I do not believe it can be proven to be true.

I believe the Catholic Church was the Church that Christ himself founded. It’s very difficult to respond to this particular objection because I’d need to know, in your opinion, what distinctive features make the Catholic Church the Catholic Church, then I’d trace those characteristics back to early Christianity.

For the purposes of this, I’ll take a handful of absolutely distinctive features that can only identify as Catholic. There are the absolute fundamentals of Christianity, such as Christ’s nature, the reality of his death and resurrection, but we both agree on those doctrines, so I’ll focus on the distinctly Catholic features of the early Church.

These include:

- a hierarchical church structure with clergy having apostolic succession,

- a belief that all Church councils are guided infallibly by the Holy Spirit,

- a belief in the real presence of Christ at the Eucharist,

- a belief in the baptismal washing away of sins,

- and the belief in confession.

All other dogmas, such as Purgatory and the Marian doctrines are not as elementary as these points, and hence the Church defined them far later in Church history.

The first feature was Church hierarchy. Did this feature exist before the 4th Century? It did. In fact, it existed one generation after the Apostles, as is clear in the writings of St. Ignatius of Antioch, who himself was a disciple of the Apostle John.

St. Ignatius wrote 7 letters as he was being brought to Rome to be martyred by the Romans in around 100AD. To use just one quote, in his letter to the Trallians, St. Ignatius says, “In like manner, let all reverence the deacons as an appointment of Jesus Christ, and the bishop as Jesus Christ, who is the Son of the father, and the presbyters as the Sanhedrin of God, and assembly of the Apostles. Apart from these, there is no Church.”

This quote clearly shows the three different offices of the early Church. It is clearly demonstrated. In fact, St. Ignatius writes to 7 different Churches across the world, and they all have this hierarchy.

The next feature is apostolic succession; did these clergymen have apostolic succession from the original Apostles? Again the testimony of the early Church clearly shows that they believed this.

In 80AD, St. Clement of Rome writes, “Through countryside and city [the Apostles] preached, and they appointed their earliest converts, testing them by the Spirit, to be the bishops and deacons of future believers. Nor was this a novelty, for bishops and deacons had been written about a long time earlier…Our Apostles knew through our Lord Jesus Christ that there would be strife for the office of bishop. For this reason, therefore, having received perfect foreknowledge, they appointed those who have already been mentioned and afterwards added the further provision that, if they should die, other approved men should succeed to their ministry.”

St. Clement, who is writing 47 years after Jesus’ death is telling us that the Apostles appointed people as bishops, and then when they died, they were succeeded by others. There isn’t a good reason to doubt this.

In fact Acts 6:6 mentions appointing St. Stephen as a leader through the laying on of hands, and the New Testament epistles are flooded with reference to appointing leaders. We have no reason to doubt Clement, therefore.

So far then, within the 1st Century, we have bishops, presbyters (which can be translated as elder or priest) and deacons, and they can trace their appointment back to the Apostles. In other words, there is apostolic succession (more on that topic here).

The next feature is the belief that the Holy Spirit guides the Church councils infallibly. Since the first Church Council, the Council of Jerusalem, is recorded in the book of Acts, it makes sense to start there.

At this council, the issue was over the necessity of the Mosaic Law for new Christian believers, and in particular the issue of circumcision. After the council has been settled, and it has been decided that circumcision is not necessary, there is simply no debate on the matter, but why is this?

I would argue that it is because the Apostles believed that their discussions were led by the Holy Spirit, and once the issue had been settled, the Apostles did not even question the validity of their decision.

St. Peter is rebuked by St. Paul because he compromises, not because he disagrees with the council. This again is in line with what Jesus says in John 16:13, “But when he, the Spirit of truth, comes, he will guide you into all the truth. He will not speak on his own; he will speak only what he hears, and he will tell you what is yet to come.”

According to Jesus, the Holy Spirit will guide the Apostles into all truth, and therefore also to his successors. It wasn’t as if the Holy Spirit only led the Apostles, then withdrew from the world. It is also untrue, as many Protestants claim, that Jesus is saying he will lead all people into all truth, and all churches.

The reason this cannot be true is that there are approximately 40,000 different Protestant denominations, all claiming that the Holy Spirit has led them, but they all have different interpretations, which contradict with other Protestant interpretation. They cannot all be correct since it is fallacious to say contradictory positions can simultaneously be true.

In addition to the apostolic age, an identical pattern is seen with other councils. That is, when a council has approved or defined a certain doctrine and condemned another understanding as heretical, that is simply the end of the matter. As St. Augustine of Hippo said, “Rome has spoken, the matter is ended.”

The next feature I will discuss is the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist. A great Biblical defense could be made here, however, in this response, I will quickly show how the early Church of the 1st Century firmly, and even aggressively affirmed Christ’s presence in the Eucharist. In his letter to the Smyrneans, St. Ignatius of Antioch writes, “They abstain from the Eucharist and from prayer, because they confess not the Eucharist to be the flesh of our Saviour Jesus Christ, which suffered for our sins, and which the Father, of His goodness, raised up again. Those, therefore, who speak against this gift of God, incur death in the midst of their disputes.”

As mentioned earlier, St. Ignatius is either writing at the end of the 1st Century or at the very beginning of the 2nd. Elsewhere, St. Ignatius refers to the Eucharist as “the medicine of immortality and the antidote against death, enabling us to live forever in Jesus Christ”. Not only does he believe that Christ really is present in the bread and wine, but he aggressively defends it, saying that the heretics (who in this case are docetists) are heretics by virtue of the fact that they do not believe the Eucharist to be Christ’s body.

St. Justin Martyr, writing in around 165AD said, “For we do not receive these things as common bread or common drink; but as Jesus Christ our Saviour being incarnate by God’s Word took flesh and blood for our salvation, so also we have been taught that the food consecrated by the Word of prayer which comes from him, from which our flesh and blood are nourished by transformation, is the flesh and blood of that incarnate Jesus”.

It can be concluded that the early Church, within 100 years of Christ’s death, believe the Eucharist to be the real presence of Christ.

The early Church also believed that baptism washed away sins. St. Irenaeus in the 2nd Century writes, “And dipped himself, says [the Scripture], ‘seven times in Jordan.’ It was not for nothing that Naaman of old, when suffering from leprosy, was purified upon his being baptized, but it served as an indication to us. For as we are lepers in sin, we are made clean, by means of the sacred water and the invocation of the Lord, from our old transgressions; being spiritually regenerated as new-born babes, even as the Lord has declared: ‘Except a man be born again through water and the Spirit, he shall not enter into the kingdom of heaven.’”

The early Church also taught the necessity of baptism, as does St. Peter in 1 Peter 3:21.

The final Catholic feature I mentioned is confession. There is a very strong reference to confession in John 20:21-23: “Again Jesus said, “Peace be with you! As the Father has sent me, I am sending you.” And with that he breathed on them and said, “Receive the Holy Spirit. If you forgive anyone’s sins, their sins are forgiven; if you do not forgive them, they are not forgiven.”

Jesus here is speaking to the Apostles after his resurrection and is giving them his own authority to forgive sins. Here he institutes the sacrament of confession, whereby people confess their sins to the Apostles and, in the future, to their successors, and they are able to forgive sins, not in their own strength, but by the breath of God, which Jesus gave when he breathed on the Apostles.

This understanding is also testified in the early Church by Hippolytus, writing early in the 3rd Century: “[The bishop conducting the ordination of the new bishop shall pray:] God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ. Pour forth now that power which comes from you, from your royal Spirit, which you gave to your beloved Son, Jesus Christ, and which he bestowed upon his holy Apostles and grant this your servant, whom you have chosen for the episcopate, [the power] to feed your holy flock and to serve without blame as your high priest, ministering night and day to propitiate unceasingly before your face and to offer to you the gifts of your holy Church, and by the Spirit of the high priesthood to have the authority to forgive sins, in accord with your command.”

To conclude this whole response then, I would disagree that the Catholic Church began in the 4th Century. The 1st Century and 2nd Century church had very Catholic characteristics.

They believed in a hierarchical church structure, with clergyman having apostolic succession back to the Apostles, they believed that Church councils were led infallibly by the Holy Spirit, they believed in the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist, they believed that baptism washed away sin, and they believed that the Apostles and their successors could forgive sins through Christ.

I would conclude by suggesting that this Church was, in fact, the Catholic Church. One could argue that this Church is different from the one seen in Scripture. After all, I’ve only argued that the generation after the Apostles were Catholic.

However, that argument is highly unlikely—after all, how could everything have gone so wrong a mere few decades after Christ? Further, this line of thinking is not even Biblical. Christ says that the gates of hell shall never prevail against the Church (Matthew 16:18), St. Paul says that the Church is the pillar and foundation of truth (1 Timothy 3:15).

If someone were to argue that the Church started off well, and then immediately became corrupt is to say that the gates of hell did prevail against the Church and, therefore, that it is not the pillar and foundation of truth. That is to contradict Scripture.

It is far more reasonable to say that the Church did not teach heresy, but that it was guarded by the Holy Spirit, and preserved from error. That Church is the Catholic Church, and the promise remains true today.

Objection 6:

Peter was married (Luke 4:38) and so the requirement of Pope’s to be celibate collapses.

Answer:

I believe here that there is a misunderstanding. The Catholic Church does not teach that every clergyman must be celibate because the Apostles were. As you pointed out, not all of the Apostles were celibate.

However, it wasn’t until the 11th Century that priests were expected to be celibate. The reason was that priests were behaving immorally, so the Pope made it mandatory that Priests are celibate.

This was to follow St. Paul’s advice where he says it is easier to give your undivided attention to the Lord if you are single (1 Corinthians 7).

Therefore, the Pope’s requirement of celibacy does not collapse. It is just a practical suggestion for clergy and, some may argue, necessary for other practical reasons.

Objection 7:

The Foundation of the Church is Jesus himself and not Peter

It is true that, ultimately, Jesus is the foundation of the Church. However, it is also true to say that St. Peter is the rock on which the Church is built upon as Jesus tells us so in Matthew 16:18.

Have you heard of any more objections to papal primacy not mentioned here? Feel free to comment and share below!

Suggested next reading: Here’s the Truth About Church Leadership…

[…] whole kingdom, and his authority was unquestioned. There was a prime minister, who foreshadows the papacy, and there was a […]